Building Power in the Environmental Movement: What I’ve Learned as a Mentor

By Angelo Villagomez

Angelo Villagomez is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress (CAP), where he focuses on Indigenous-led conservation. Born in a village on an island in the western Pacific Ocean next to the Mariana Trench and trained in Western scientific methods, Villagomez is a conservation advocate who uses Indigenous knowledge and values and the scientific method to address modern threats including habitat loss, fishing, and climate colonialism.

In his blog, he describes how mentoring creates new leaders and how mentors can learn and grow from these relationships.

Q: Why did you start mentoring others in the environmental sector?

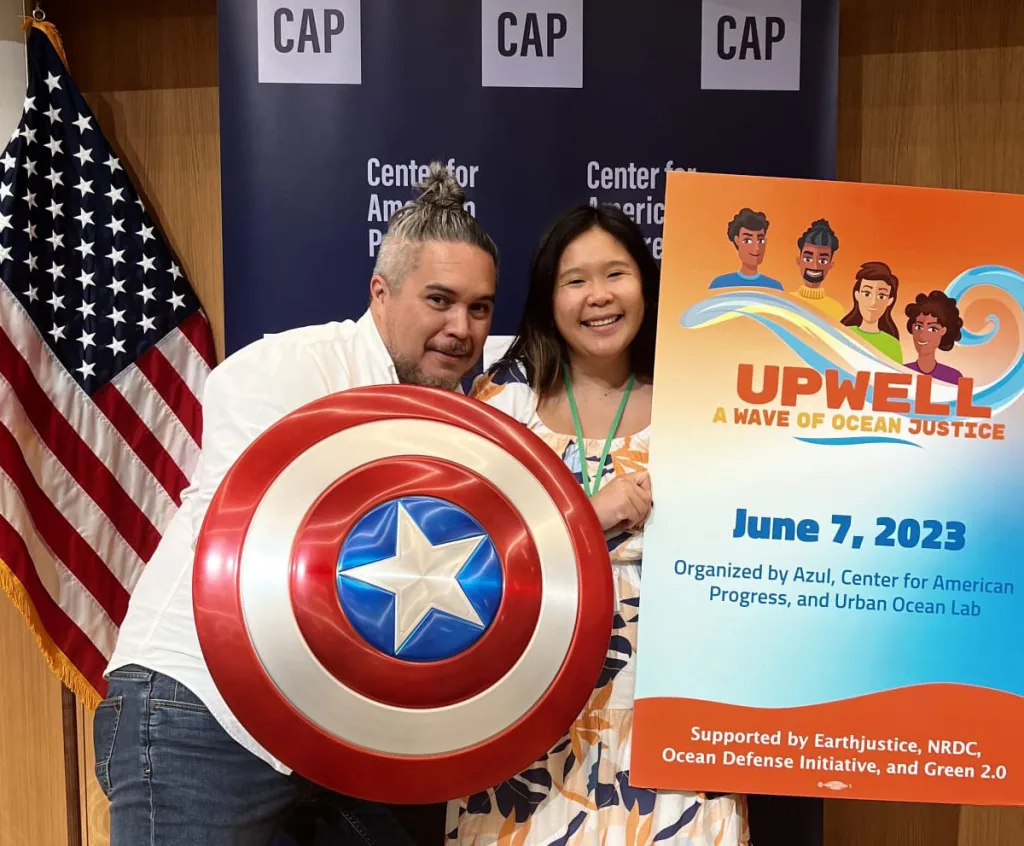

A: Part of the answer is I got old. The opportunity to mentor came into my life and I just did it. With Raiana, it was starting and growing the first employee resource group for people of color at Pew. This was before the summer of George Floyd, and discussions about racism and belonging in the workplace were not necessarily welcome in a corporate setting, and we learned a lot together. With Kat it was helping to co-found and grow Upwell: A Wave of Ocean Justice in coalition with several partners, including Green 2.0.

In both situations we were colleagues of different seniority levels in different silos of the organization, and the mentorship emerged naturally as a part of a project we worked on together. And in both cases the mentorship arose out of a challenge to the status quo. We were building a movement together, not just advancing a career.

Q: What have you gained from being a mentor?

A: I have brilliant and very patient mentors in my life, and I think there is a bit of a passing of the baton when it comes to mentorship. Mentorship and creating pathways to transition leadership doesn’t just ensure that an organization or movement remains durable, it also ensures that your legacy continues, so there is a part of it that is selfish. But ultimately, creating new leaders and letting go of control builds power in a movement.

Q: What surprised you most about your journey as a mentor?

A: Being a mentor for someone else can be a way to reflect on your own earlier experiences, for better or for worse. With Kat and Raiana, cultural identity played a big role in our mentorships, even though we are from different heritages. In different ways, our mentorships focused on creating belonging for them, but also for other women and people of color in the conservation movement.

As a person of Chamorro heritage, for much of my career I observed that the inclusion of Indigenous peoples in too many conservation efforts fall into tokenizing “noble savage” tropes. This was often difficult for me. As an example, at an event, the Indigenous people would be invited to sing a song or say a prayer, but only White people gave speeches – or got paid. When I pushed back against these practices, sometimes there was nobody above me who understood my perspective. As a mentor, even if I can’t get an institution to change their bad practices, I can now be that supportive person for someone else and help them navigate the dynamic.

Q: Can you share something you’ve learned from a mentee?

A: I can remember words that some of my mentors said to me decades ago that still guide me. Even so, it was a surprise when mentees repeated back my own words to me. Words are really powerful and can be used for good and can inspire. But it goes the other way, too, and I’ve not always used the best words. Raiana and Kat have had the patience to help me to better communicate with people who are younger or women.

Q: How does mentorship improve opportunities for connection and increase inclusion in the environmental sector?

A: Done right, mentorship helps mentees see themselves in future and current leadership roles. A good mentor can help you feel valued in the workplace, feel included on teams, and can help to deliver opportunities for learning and growth. It builds trust between people, helps the mentee learn to wield power, and ultimately keeps people from dropping out of the conservation movement.